Choosing multiple adventures

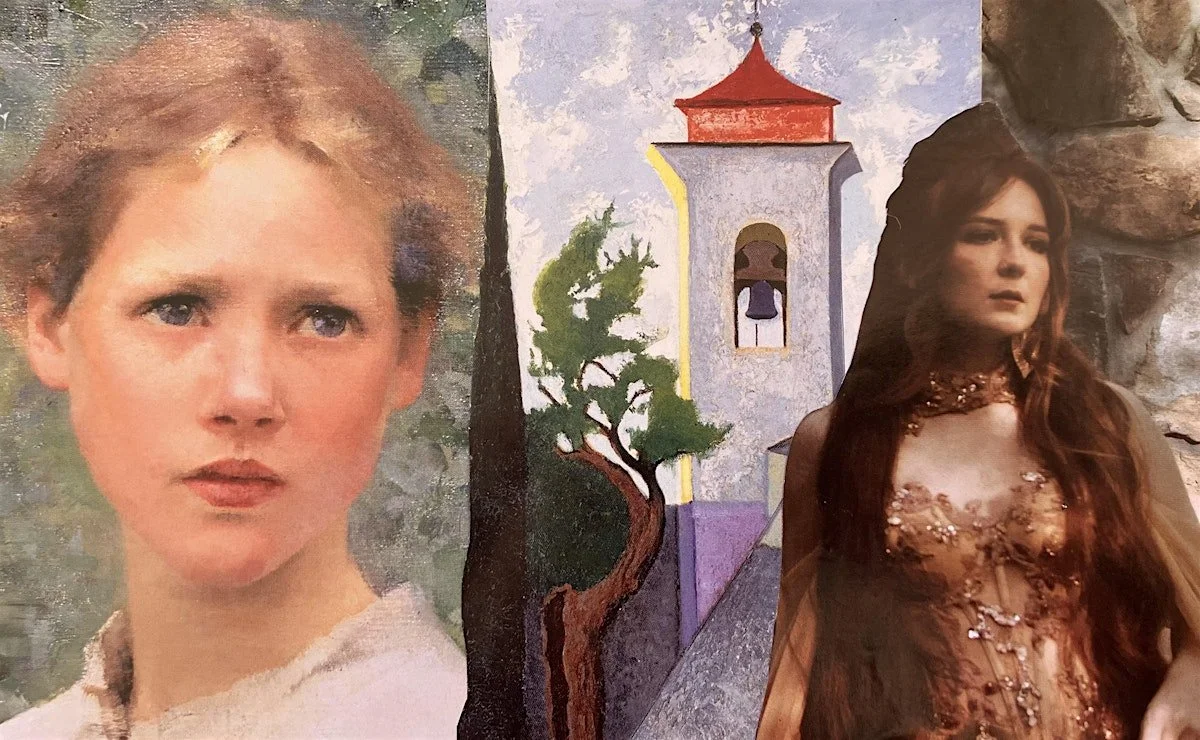

My SoulCollage® card for my “Exploring Rapunzel” workshop, 4 October 2025

Everyone knows how Rapunzel ends: a man shows up at her tower and rescues her. Or, in the case of Disney’s retelling of Rapunzel, Tangled, a goofy outlaw boy shows up and she half-saves herself. But what I wondered, as I dug into a Sicilian version of the tale for a recent SoulCollage® workshop, is why that framework of her escape has such a stranglehold on our culture.

Some of the fixed-ness of Rapunzel comes from Disney. Some of it comes straight from patriarchal ideas, that women need men to save them. Some of it is tradition, the way we think fairytales need to unfold. And, I suspect, some of it is rooted in how reassuring the idea of being rescued from a scary situation feels.

“So, why not give her a choice?” I thought, preparing my story. “What more could a girl traded by her mother to a witch for some stolen fruit, then imprisoned in a tower—basically, if your whole childhood was a prison of some sort, what would you want?

Choosing your own adventure

…Now he believed that where there was a key, there must also be a lock, so he dug in the ground and found a little iron chest. "If only the key fits!" he thought. "Certainly there are valuable things in the chest." He looked, but there was no keyhole. Finally he found one, but so small that it could scarcely be seen. He tried the key, and fortunately it fitted. Then he turned it once, and now we must wait until he has finished unlocking it and has opened the lid. Then we shall find out what kind of wonderful things there were in the little chest.

Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, the Golden Key, https://sites.pitt.edu/~dash/type2250.html

From the second edition onward this story has occupied the last position in the collection (excluding the appendix of ten Children's Legends). By closing their collection with this enigmatic tale without an end, the Grimms seem to be saying that folktales, too, are endless. There is no final word.

D.L. Ashliman analysis of The Golden Key, https://sites.pitt.edu/~dash/type2250.html

As any folktale/fairytale scholar will tell you, historically, folktales did not have fixed endings. In the snippets above, we see the Grimms ended their book of folktales ambiguously, and as D.L. Ashliman notes, this is a nod to folktales’ original spoken origins. Spoken-word storytelling is an ideal medium for experimentation based on mood, audience, time of year. Even once the oral tales were written down, by folks like the Brother Grimm, they still made edits. (To use a dramatic example: originally it’s Snow White’s mother who orders her death, but society balks at acknowledging that sort of maternal abuse, so the character became a stepmother.)

Even reading from a published book, I suspect many parents reading these stories aloud change their endings, especially at bedtime. But once Disney got ahold of popular folktales and fairytales, they got lodged in our brains as THE correct versions. Between the witty songs and the richly drawn worlds, that makes sense. But it can also be hard to have a conversation about, say, the different ways Sleeping Beauty is told in cultures around the world, when Disney’s is seen as the one true version.

And yet, much like any widespread cultural phenomenon, there is pushback to Disney as arbiter of fairytale lore.

One of the first ways people around my age (aka the Oregon Trail generation, or more broadly, kids of the 80s/90s) learned about storytelling was from Choose Your Own Adventure books. If you’re not familiar with CYOA books, they were novel-length books for children written in the second person, where the character, referred to as “you,” chose how to act, and thus determined the outcome of the book.

Leslie Jamison, an essayist and memoirist, describes the draw of Choose Your Own Adventure books this way:

You didn’t necessarily identify with the unnamed “you” who starred in each book. It was more that each protagonist offered you an alternative to yourself, or forty alternatives to yourself. The second person was less like a mirror and more like a costume. Reading these books wasn’t about the pleasure of “relatability” but about something opposite—the pleasures of distortion, recklessness, and multiplicity. Every protagonist contained multitudes, a set of contradictory impulses that didn’t have to cohere: The self who explores the haunted house and the one who stays behind. The self who confronts the ghost and the one who runs away…

When you read these books as a child, your process was always the same: you started by following your intuitions, trying to approximate what you would actually do in these far-fetched situations, and—once you’d reached that first ending, the one you probably deserved—you let yourself try anything you wanted. You let yourself make reckless choices that ran counter to your intuitions in every imaginable way. It was like wearing brave-person drag.

In other words, these books were consequence-free romps through a life of possibility and adventure. They may not have had the most brilliant writing or characters we’d remember forever, but they created pathways for any kid–even if they weren’t particularly bookish–to explore what could happen next, if they only made a different choice, instead of just absorbing a story as written that has all the decisions made in advance.

For bookish folks like me, there is immense pleasure in submerging yourself in a good story. Following the characters, rooting for their happiness, or cheering on their downfall. I am one of those people who tends to read fiction to figure out my real life, even when I’m not totally conscious that that’s what I’m doing—rereading books, staying in one genre for a stretch of time…and then suddenly something clicks! I suddenly know what I need to do, inspired by imaginary characters and situations.

But when you aren’t just immersing yourself in someone else’s narrative, when you yourself are telling a story, or involved in a collective effort to tell a story, your mind processes the twists and turns differently. You become part of the story by telling it, and it matters a bit less what the author meant to happen–you get to choose what resonates within you.

Transformative works: midrash, fanfiction, and beyond

To many readers, living in a culturally Christian context, this next bit may seem pretty wild/unfamiliar/sacrilegious. Did you know that in the Jewish tradition, rewriting what “really happened” in the Bible is not just kosher, but encouraged? It’s called midrash, and it’s basically Torah/Tanakh/Talmud fanfiction. As Reba Carmel explains,

the word “midrash” is derived from the Hebrew root drash -- study, inquire, seek, explain, investigate, interpret. The sheer number of verbs that actively describe the process of creating midrash speaks not to uncertainty but to vibrancy. These are not stories hidden away for centuries in clay pots, only to be discovered and enshrined behind glass in a museum. Rather, the multiplicity of descriptors speaks to the Jewish people’s relationship with the foundational literature that has been transmitted.

Midrash is our persistent attempt to create meaning — yet the question remains, meaning out of what and for whom?

What’s more, “not only are Jews encouraged to reintepret our religious texts this way, it’s commanded,” Rabbi Rachel Barenblat teaches. “Torah itself urges the reader to find a voice, since one of the last commandments in Torah is to write one’s own Torah. (Deut. 31:19) ...The canon is never closed. New interpretations are always being created.”

In other words, Jews are supposed to think about why things happened, why Biblical figures act in certain ways, whether they were right or wrong, etc. This collective tinkering and figuring out has created vast bodies of work, incorporated into written texts long ago, and into sermons and books to this day.

Midrash and fanfiction, be it reinterpretations of Pride & Prejudice or rewriting tv shows so your preferred characters get together, share another key trait. Reading a Choose Your Own Adventure book is largely a solitary activity. But writing midrash or fanfiction happens in community. You’re talking to your peers, whether irl or online, fighting about interpretations, mocking the most bizarre works, lifting up each others’ writings in the new worlds you’re collectively creating within established worlds.

And sometimes, these innovative retellings even make it to the big screen. One of my favorite movies in recent years, the 2019 Little Women movie by Greta Gerwig, plays with the controversial ending of the work–namely, Jo marrying Professor Bhaer. I was never a fan of Jo being married off, so I am exactly Gerwig’s ideal audience. In her version, we watch Jo arguing with her editor, fighting to leave her heroine unmarried at the end. We see her watching her book be printed, and understand that her journey to becoming a “published freaking author,” to quote Jane the Virgin (my current multiple-stories-simultaenously rewatch), is her happily ever after. Spliced within that storyline is the alternative from Alcott’s book, where Jo marries. We see Jo, encouraged by her sisters, run after Professor Bhaer, marry him, and end up in the middle of a party, surrounded by all of the sisters’ children, their husbands, and their parents (save Beth, of course).

Gerwig does not choose Jo’s ending–she lets us choose. Then, when you rewatch the movie with the ending in mind, you realize there are threads of both endings woven through the movie, so that both are equally supported by the movie’s text. The Jo who runs through the streets who gets caught up in a wild dance becomes an author. The Jo who leaves the city to return to her family despite her professional commitments, who reconsiders accepting Laurie’s proposal is the one who gets married. Both versions are easily possible within the original text, and which one you root on has more to do with you than Jo March or Louisa May Alcott.

To quote Rabbi Barenblat again,

In fanfiction, as in midrash, we look at the existing story through new lenses. We embroider new ideas onto the text, or highlight themes which were present but hidden. We give voice to the voiceless and make sense of the senseless. We tell our truths, and we frolic in the playground of the text and its possibilities.

We write fanfiction, as we write midrash, both out of love for the texts we’re given and out of frustration with those texts.

What’s more, as Kaylee Nichole Lopez-Nunez notes

From an anthropological perspective, written fan fiction exemplifies the enduring human need to tell stories as a survival mechanism — a means to navigate complexity, forge connections, and explore identity. By examining fan fiction through the lenses of mythology and cultural world-building, we can appreciate how it serves as a vital space for creativity, community, and reflection in our rapidly changing world.

Fanfic of all stripes is a lot more than people shipping weird couples on AO3 in that light, isn’t it?

Rapunzel, reconsidered

To me, Rapunzel is, at its roots, a story of the twisted places a rash decision can lead you. After all, the version I chose, from Sicilian folklore, starts with a craving for some jujubes (also known as red dates) that snowballs into giving up your unborn child to the witch you stole the jujubes from. But Rapunzel has no choices. She stays with her mother until she’s given to the witch, then she stays in the tower until the prince comes to take her away. So many fairytales feature dire situations for young heroines, but even when you’re running from the Huntsman in the dark forest as Snow White, you decide which twists and turns of the path you take. You can imagine your feet tripping over tree roots and you holding your breath in the hollow of a tree to hide. Even in tales where heroines have less power—take Cinderalla, for example—they can beg to go to the ball, escape, meet a fairy godmother. There are so many small freedoms these characters steal for themselves before their big escapes, but Rapunzel’s position in a tower takes away most of her opportunity for even small testing of the boundaries.

Who are you if you have no freedom to test your wings? Would the traditional version of Rapunzel, where she’s rescued by a prince and immediately put inside a castle with new responsibilities as princess, and later queen, free her in any way? We need only look to the example of Princess Diana or Meghan to see becoming a princess as a prettied-up cage fraught with danger and oppressive control.

It is ironic that folktales and fairytales, which originally gave voice to the voiceless, to women in particular, have now become so rigid that they only have one answer, and that answer is often exchanging one cage for another.

But we also live in a world where we can rewrite the story however we want, and find a community of people who are eager to hear our new takes on canon. In a world dominated by constant repeats of popular IP (Star Wars, Marvel, tv show remakes), rewriting old, classic tales has subversive power. We get to fracture fairytales and create Wicked. We get to give tv shows cancelled after 1 or 2 seasons by Netflix satisfying endings. And we get to put a bit of ourselves in those stories, carry them around inside until they are also us, put out into the world, waiting to be discovered.

To end, I love this description of her Little Women by Greta Gerwig—more cubist stories in mainstream media, please?

But Gerwig’s fragmented, poetic take on Little Women also defies easy categorization. As she put it on Vanity Fair’s Little Gold Men podcast, “What I was always looking for was this cubist, intuitive, emotional, intellectual kaleidoscope of authorship and ownership of text and of character. Everything had to be multiple things, it could not ever just be singular. I had to have a multiplicity in every moment, every line.” So in many ways, Gerwig is trying to deliver two finales at once, both the novel’s conventional happy ending and a different take on what happy endings can look like. “The hat trick I wanted to pull off was, what if you felt when she gets her book the way you generally feel about a girl getting kissed?” Gerwig explains. “So it’s not girl gets boy, it’s girl gets book.”