Getting stuck is the point

One of my surface design patterns, featuring golden dandelions and dandelion clocks.

The only way to learn to make a thing is to make it.

Even if it’s bad.

Especially when it’s bad.

Even when you feel stuck, blocked, frozen with imposter syndrome.

You might ask yourself “couldn’t I just take a shortcut with AI?”

Everyone else is doing it, and their results don’t seem too bad, to me…

Leaving aside the ethical and environmental concerns, I want you to think of your favorite book, movie, song. Where does the magic come from?

Back to getting stuck: why do most artists think it’s a necessary part of the process? Seems counterintuitive when you first consider it, maybe. Being stuck usually means you’re not creating, after all.

Getting stuck exercises your critical thinking muscles. Making artistic decisions, and reevaluating your creations with new eyes–those require critical thinking. (What’s more, critical thinking can get you out of some jams in the rest of your life!)

Yes, critical thinking is often used as a buzzword without much substance. But I have an education background (I used to teach college poli sci), and critical thinking was the number one thing I wanted to teach my students:

How do you figure out what a text says?

How do you analyze it, and what’s your position once you’ve done so?

What’s more, is what the author had to say important?

Critical thinking is essential to reading the news, evaluating whether a blog post about a celebrity or a big news event is real or fake, or even to looking at pictures in magazines, which are likely photoshopped. (And, hoo boy was it a thing to be a teenage girl in the 90s when people weren’t really talking about photoshopping models, but insisting our bodies were wrong if we didn’t look like faked images.)

I recently came across this really neat infographic online as a part of this article. The graphic was created by a high school AP history teacher, Dr. Robert Naeher, and shows the questions he would ask his students.

A diagram of critical thinking steps by Dr. Robert Naeher

But this model is from a history teacher—can it help us understand creative pursuits? What if we could apply this critical thinking model artistic challenges? How could it get us unstuck?

Let’s take an art problem I had this spring: how to capture the profusion of April dandelions?

Dandelions are, to most, not that deep. They don’t have world-historical importance, save as part of ecosystems and folk health remedies (my grandmother swore by dandelion soup!). But I spent a week completely obsessed with this puzzle, and I know it stretched my brain and my abilities to follow my critical thinking to the end result.

What do we see?

This spring, all of a sudden, my entire world was full to brimming with dandelions. Bright yellow faces turned toward the sky, little bits of yellow peeking out of buds, and of course dandelion clocks everywhere.

Me peering at the camera with some dandelion clocks

They were so there that I couldn’t stop thinking about them—how could I make interesting dandelion art? I don’t make photorealistic art, but I also wanted to expand my range. Most of my art is flowy and textured, but I wanted to create stylized, graphic dandelions. In the end, I decided I wanted to create art deco dandelions.

2. What do others see?

Art deco is sleek and geometric. You can see great architectural examples at the Empire State Building, the Chrysler Building, and Radio City Music Hall, among many others. They’re iconic. But it has strong stylistic rules, and breaking them = not art deco.

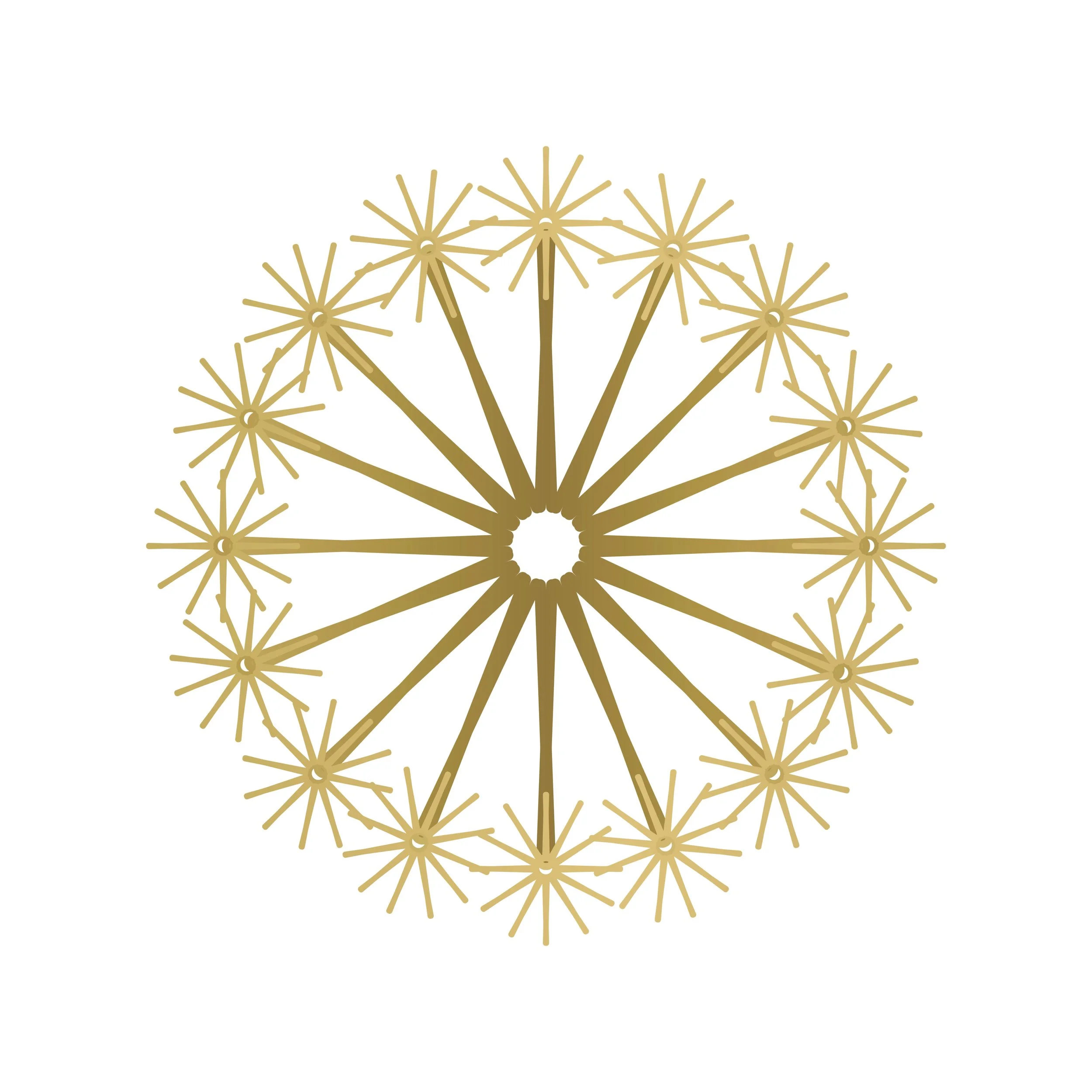

To see like an art deco creator, I needed to work in angled lines and/or strong curves, with repeating elements. So I built this sunburst-inspired dandelion clock, added gold foil to the linework, and was delighted. It definitely was art deco-inspired!

A symmetrical golden Art Deco dandelion clock, with darker gold in the center.

3. What didn’t I see?

But…the coolest part about a dandelion clock is the way it blows away in the wind, right? Being a kid and puffing on it, watching the seeds on their parachute-stems fly into the wind is definitely a childhood memory for me. So I couldn’t stop with just a dandelion clock: I needed to make one that showed the motion.

4. What did I expect to see?

Frankly, at first I didn’t think this would be a problem—I could just float a seed off sideways and call it a day. But showing motion in a geometric shape is a lot harder than it seems, turns out, because this method broke the repeating pattern.

A test pattern of the same golden dandelion clocks on a white background with one seed stem flying off. It’s not great.

I started the artistic equivalent of the kid blowing off the stems, moving them every which way. After what felt like a million drafts, I felt like I broke my brain.

Chaotic dandelion stems flying off—not a great piece.

I honestly thought about just working with the two designs I had at that point—the complete clock and the dandelion flower—and giving up on the motion. But then I’d walk away and go “well maybe they could just be the seed stalks floating about.’ They ended up looking like distorted fireworks.

This is the place of getting stuck. The place where you can choose to keep puzzling, or give up.

And I’d give up on it, and say it wasn’t my thing anyway, that art deco isn’t my style. I was 3-4 days into dandelion clock obsession, with hours of fiddling about on my ipad only to stalk off aggravated, ranting to myself about how much I hated geometry and trig in high school and I did not become an artist to get to do MATH of all things.

5. What isn’t there?

But sometimes what’s missing is looking at a problem from a new direction. In this case, what I needed was a new metaphor. I was failing at building moving DANDELION clocks; I needed to build dandelion CLOCKS instead. This metaphor of clock-making gave me the idea of having symmetrical gears that moved together inside a circle. I could make an art deco pattern if I just kept the motion more contained.

6. Who set the scene that I see?

My imagination and my previous art-making determined how I was able to problem-solve at first. But between the constraints of art deco style, and the metaphor of the clock-making, I now had a model to work within. It wasn’t my usual style and that’s why it felt like magic.

7. What are the facts?

But I was still struggling. I moved the seed stalks in, I moved them out. I organized them in different patterns. But no matter what, it wasn’t immediately obvious that they were moving…until I went back outside and really looked again.

Turned out I missed something about the structure of the dandelion clocks.

Before the seed-parachutes fly into the air, they’re tethered to the rest of the plant. Without the center providing the origin point, the seeds couldn’t fly. What’s more, they couldn’t appear to fly. The motion was defined by where they started.

So I added the center, and all of a sudden the clock clicked together. All of the seeds had to be close enough that you could tell they were once attached, but staggering them a bit shows that they’re starting to move. Bonus, it even looks a bit like a mechanical clock in the center.

The seed stems begin to detach from the center, finally!

And voila! It turned out really cool, and the circle metaphor I came up with from the clock analogy created more ideas and combinations, until I had this, my favorite piece of the collection, which is basically a dandelion spirograph.

So what were the steps here? How does this apply to your life, assuming you don’t stay up nights worried about dandelions or teaching the machinations of history to your students. Here’s my process, expanded.

I found inspiration in the outside world.

I had to decide how to translate it into my own thing (art deco dandelions)

Then came brainstorming ideas, which held together pretty well for the first design

But then I had a new idea—introducing motion—and had to expand my range as I became increasingly enthusiastic.

…at which point I hit a pothole I couldn’t see a way out of

This is the place of struggle. This is the place where you want to get someone to do it for you, the moment you’re stuck and wandering around like I did in college, asking if anyone wanted to write my paper for me. (Which of course was not what I wanted, nor was it possible, but it made me feel a tiny bit better to wander around and bitch about it.)

This is the point you have to decide if whatever you’re doing is worth it. And, likely, your commitment is going to waver.

Going back to the AI question: outsourcing your critical thinking gets rid of the friction that leads to new ideas. At best, AI can mash together existing (stolen) art, but it can’t create a brand new idea, a brand new thing. It regurgitates and recombines, but it can’t be struck by the lightning bolt of genius.

Being stuck is how I ended up with a brand new thing, how I expanded my range of what I’m capable of. If I hadn’t tried something new, I would still be the person who doesn’t do art deco, just because it doesn’t come naturally.

Trying a new food or visiting a new place or meeting a new person can all be awful. Some new books and new songs and new tv shows are horrifyingly bad. But experiencing the good versions of all of these people, places, and things expands who we are, how we define ourselves and what we’re interested in, and how we want to be in the world.

There’s no easy A to B roadmap to think through a problem or create a thing, even smaller things. If you try a new path out walking, you might get lost. If you try to change a recipe, you might end up ordering take out with a lot of scary looking pots and pans to wash. If you take a beginners’ dance class you might trip over your feet (and your dance partner’s feet). You will definitely feel lost and aggravated a lot of the time if you start learning a language or playing a new sport or renovating your house.