Poetry: to open you up and make you feel less alone

Me aboard the boat to Bremerhaven, very close to the dock. I am windswept and wet from the journey, but ecstatic nevertheless.

Here, where I am surrounded by an enormous landscape, which the winds move across as they come from the seas, here I feel that there is no one anywhere who can answer for you those questions and feelings, which, in their depths, have a life of their own…

Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet, p. 31, Worpswede, near Bremen, 16 July 1903

This passage in Rilke’s letters is from a collection of responses to an angst-ridden 19 year old poet named Franz Xaver Kappus. Rilke was generally a good correspondent, but when he discovered that Kappus attended Rilke’s alma mater, Lower Military School at Sankt-Pölten–a place/time in Rilke’s life that he described as “one long terrifying damnation”--he took extra care to advise Kappus well (Stephen Mitchell’s forward).

I have placed another quotation from the same letter later in this piece. You may well recognize it. But what struck me about the quoted passage above was that it expresses a feeling I once had, very near to where he wrote it.

In July of 1903, Rilke is traveling Europe, often while sick or for health reasons. In July of 2009, studying in Germany during my PhD program, I also could’ve used a rest cure. My body didn’t much like the town I studied in, Göttingen, and I suspect my school/housing complex, gorgeous as it was, had mold, making me even sicker.

But most of all what I was was heart-sick. My grad program was not going well (when I say my advisor and his wife took out a hit on my career for disagreeing with them, I am not exaggerating). That spring I had to completely change my dissertation field, choose a topic I was not super enthusiastic about, and then I found funding and fled to Germany to study German (which also didn’t agree with me, much as I love grammar).

But man oh man did I love Bremen. It is, to this day, the only place in Germany I ever felt good. We went on a school trip, and the town was charming (lots of statues of the animals from “The Town Musicians of Bremen,” which is a fun folktale). We then took a boat to Bremerhaven, and spent a day there at a museum of emigration.

I may have loved Bremerhaven, but I was still an angsty chick in the Emigration museum.

But what I still remember so clearly, 16 years later, is the absolute freedom I felt on the boat. Part of it was probably the weather–when I do an image search for the route, it doesn’t look like I remember. But it was raining that day, so most everyone was hiding below deck. When I look at my pictures of the journey, I see the stark gray day, my hair damp, half-wavy, half-limp.

But I sat there, alone, my face to the wind and rain, and arrived in Bremerhaven feeling like a different person. I see my smile and my posture, open to the world.

That is exactly the prescription Rilke would’ve written for my angsty 25-year-old self. To just sit in the enormity of the landscape and the elements, and be. Not try to make it anything else, not try to make myself anything else, just experience.

And, sure enough, I still remember the feeling on that boat 15 years later, when so much of that summer has been lost to memory…

And poetry to steer your life’s ship into your future, to help you live the questions

…I would like to beg you, dear Sir, as well as I can, to have patience with everything unresolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves as if they were locked rooms or books written in a very foreign language. Don’t search for the answers, which could not be given to you now, because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps then, someday far in the future, you will gradually, without even noticing it, live your way into the answer.

Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet, p. 33-34

Poetry, art, nature: these are the well-worn ways to dive more deeply into oneself. These days, I avail myself of all three regularly.

But in 2009, poetry was mostly a non-option for me. I loved novels. I loved nonfiction enough to get a PhD in political philosophy. Most of all I loved immersing myself fully in an alternate world for hours, days, years at a time. I reread my favorite books endlessly; I used the ones I knew best to learn to read in French.

But poetry is short. How do you get lost in so few words?

It felt opaque. Stylized in forms I didn’t quite understand.

It felt like a medium for other people. A form I could not understand, save a few exceptions. (I would discover six months after my trip to Bremen that one of those exceptions was Rilke, but I still couldn’t make it through a whole book of his poems, just a few favorites.)

So I kept to my half-dozen poems, told myself poetry wasn’t for me, and kept on going.

And then the world shut down.

Everyone changed in 2020, but I’m immunocompromised, in part from past viruses (hello long Epstein Barr). I spent my youth being unexplainably sick, so I did everything–and am still doing–everything I possibly could to avoid illnesses that could cause additional disabilities.

So I turned to Emily Dickinson.

Emily would get it, my fear of the dangers of the outside world. She spent most of the latter part of her life confined to her house.

But she also celebrated the simple pleasures–the flowers, the seasons, the sun, moon and stars. Those were still available while being careful, unlike most modern entertainments (outside streaming videos, which I did a ton of too!).

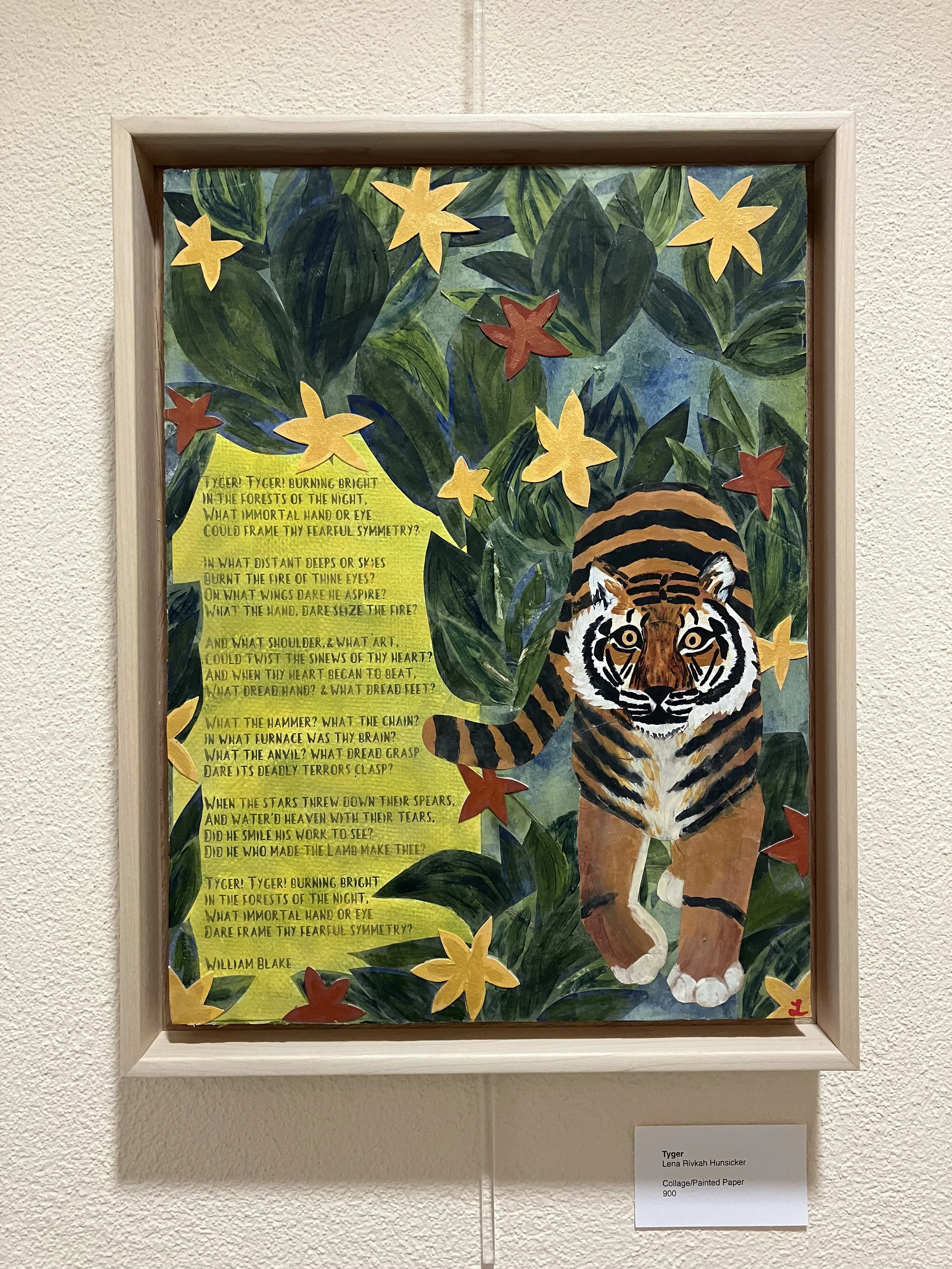

I began making poetry art, which took the form of painted-paper collage on wood panels, that I inscribed with poetry over the artistic interpretation.

Suddenly I was hooked on poetry.

Fascinated by what I could learn if I turned these poetic vignettes into colors and shapes.

I had to buy tiny scissors to cut and assemble hundreds of flowers, of leaves, of sky-scapes and animals.

And, it turned out, poetry was the stuff of the life I was living. I had turned almost totally inward, and was living my life most fully inside my soul.

One of my favorite pieces: Tyger, an interpretation of the William Blake poem, complete with a font I invented and an awesome collaged tiger.

I wanted to make poetry that was public domain, so I discovered all sorts of weird and interesting poets I had never heard of. I would love a dinner party with Emily Dickinson, Edna St. Vincent Millay, and Emma Lazarus, btw.

Learning to live inside poems, to transform my experience of them visually as a way of understanding their meanings to me: it seems to me to be the same as Rilke’s exhortation to live the questions. Poems couldn’t answer my problems. They couldn’t extinguish a virus. They couldn’t make me healthy.

But they were keys to the “locked rooms or books written in a very foreign language.” They have become, by my living them with a paintbrush and scissors, answers to my questions about how to live. These artworks even became my first art show (webpage and video showcasing it can be found here).

Yes, poetry can seem obscure, impenetrable, an artificial exercise in organizing weighty words.

But it can also be a clarion call at dawn, a carefully sewn together book of private work that you never show anyone (more on Emily’s hidden books here!).

Poetry can be a window to a new world of questions.

And isn’t a question above all a window, a door, a secret passage, a rift in the known universe?

Isn’t that why Rilke emphatically reminds his young friend that the answers may be late in coming and surprising, because you must cross those thresholds to know where they lead?

Above all, isn’t navigating the unknown, being awed by the enormity of the landscape, and digging within, the only way to find the answers?

And now to close with my first favorite poem by Rilke, Archaic Torso of Apollo:

We cannot know his legendary head

with eyes like ripening fruit. And yet his torso

is still suffused with brilliance from inside,

like a lamp, in which his gaze, now turned to low,gleams in all its power. Otherwise

the curved breast could not dazzle you so, nor could

a smile run through the placid hips and thighs

to that dark center where procreation flared.Otherwise this stone would seem defaced

beneath the translucent cascade of the shoulders

and would not glisten like a wild beast’s fur:would not, from all the borders of itself,

burst like a star: for here there is no place

that does not see you. You must change your life.

P.S. Is anyone surprised that Rilke, Emily Dickinson, and I are all Sagittarius-born? Because y’all shouldn’t be ;)